In short, yes.

But I think there is a confusion about what this means for a writer. This is a shorthand that editors, tutors, critics and book coaches use but I’ve started to realise that’s there a misunderstanding here.

Writers are frustrated that they must start their books in a skyscraper scaling action sequence a la Tom Cruise or with a character running down the street chased by spies, their book beginning in medias res. This isn’t what an editor, book coach or workshop leader means by ‘start your novel in action’.

If you replace the idea of ‘in action’ with start with an ‘exciting’ opening, we get closer to the core of this advice. However, I can see how exciting might also translate to big car explosions and the aforementioned Tom Cruise skyscraper.

But let’s reframe that idea with starting your book with an exciting opening.

An exciting opening will ask a question of the narrative (and in doing so, the reader). It might be a question that ultimately the novel answers by the end, but often times, it’s not. That question will change and stretch as the pages turn.

In Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived in the Castle, chapter 1 begins:

We very quickly get the narrator’s voice: she has a direct albeit strange way of speaking and by telling us immediately her world view (it’s important for the reader to know her werewolf status and that she’s a bit obsessed with death-cup mushrooms), the reader just knows that Mary Katherine (or Merricat, as we soon learn) will be a vivid character to follow.

The opening is lively, has energy and it has set up questions that the book will then go on to explore and answer.

- Everyone else in the family is dead. Will this be important?

- Why can’t Merricat return her library books? Does this have to do with the family? Their deaths? Her behaviour or world view?

Jackson has set up so much here in 2 short paragraphs. Even though Merricat isn’t running down a street or robbing a bank, she’s very much in action.

With starting in action (or an exciting opening), things are happening. You should think of:

- Character

- Voice

- Place

- Mystery (that’s the question, doubt or curiosity you’re planting for the reader)

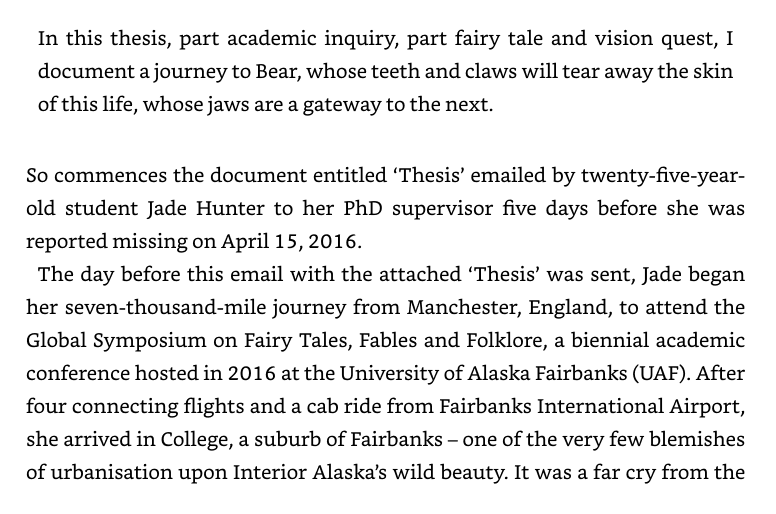

In Gemma Fairclough’s Bear Season, chapter 1 begins:

We have a brief excerpt that we are told is an academic thesis. It’s very unusual in its language and imagery – right away, we know this isn’t a ‘normal’ thesis.

The narration has a certain quality to it, almost as if it’s reporting on a real event. This makes sense as readers soon learn that Bear Season takes the form of found texts and fabricated citations (Think: His Bloody Project). Eventually we learn that the voice is a journalist’s who is digging into the disappearance of a young PhD student.

The novel starts in action:

- A mysterious document has been found

- The writer has disappeared after travelling half-way across the world

- She disappeared in a remote and enigmatic place (rural Alaska)

- Why was she attending a symposium on fables and folklore? Will this story have a reality-based solution or something more unreal?

Notice how the opening actually does a lot of telling but it feels energetic. It poses a mystery and a few questions immediately, throwing the reader into action. It ultimately shows us the world.

We’ve looked at two examples that are voices setting up their novels but let’s look at one where the character is moving around his space.

In Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis, the main character has transformed, literally. Now, before I get started here, I want to point out that it begins with a character after he wakes in the morning. You’ll hear advice about avoiding starting your book with characters waking and I strongly agree with this. If you need to have your character wake up, look at the alarm clock, ask their partner for coffee and then scroll through their phone for an hour, write it but then chuck that out and start your book in the next chapter when they’ve transformed into a large and horrible vermin.*

The Metamorphosis is not about waking. It’s about disruption and transformation. Before he wakes, Gregor Samsa, even in his dream state, is before. His after is the transformation into a horrible vermin in sentence 1. His world has become disrupted right away.

In paragraph 1, the question the reader could wonder is: Is this real? Is he in a dream state? A nightmare?

But by paragraph 2, Kafka assures us that ‘It wasn’t a dream.’ The real horror then begins for poor Gregor. He’s an average man, a travelling salesman, who we presume must leave his room to attend to his job and life. But now he’s stuck: What is he to do? Is this permanent? Why is he a giant bug?

Even though Gregor is in an enclosed space, right from sentence 1 he’s started in action.

- He’s had a troubled night

- He’s awoke transformed into a large vermin/bug

- His life is turned upside down and he (and the reader) wonders how he’ll even survive

- How will he leave this room? Will he even leave this room?

What to avoid…

So, we’ve looked at examples and elements that make a novel’s beginning start ‘in action’. (By the way, did you notice that each of these examples start from the very first sentence? There’s no dawdling.)

As an editor, I read a lot of openings but you know what I don’t read a lot of – the rest of the manuscript. That’s because many people are either starting their novels in the wrong place or they left their very first draft opening even though they’ve revised the rest of the novel.

While writing, if you need to get started by having your character look around, walk to the Londis and pick up a pack of cigarettes, that’s fine! But when redrafting, how about have them at the Londis buying their cigarettes when something strange and dangerous happens to totally disrupt their world? You don’t even need them observing anything at the corner shop; it could be something as direct as: I walked into Londis for a pack of Pall Malls when a woman covered in blood ran into me.

Stylistically simple, yes, but in one opening sentence, you set up so much: Who is the ‘I’? Do they normally smoke Pall Malls? Is this what they do every day? Are they a creature of routine? WHY IS THERE A BLOODY WOMAN RUNNING INTO THE LONDIS ON THE CORNER?

Remember, if you’re opening isn’t asking a question of the reader, it might be time to revise.

Also to consider:

- Avoid a prosaic opening. Meaning: we’re not here to get a general observation of the space. Think about what makes this moment different; this space special.

- Overwriting. People want to get across their writing style but, in reality, this often plays out as stuffy and stodgy. If you find that you’re saying a lot without actually saying a lot, this might not be the best opening.

- Avoid starting in a dream sequence. Yes, there are successful authors who pull it off, but starting a dream sequence often ends up with lack of momentum and a confused reader.

- No alarm clocks or mirrors. Writers who are at the beginning of their craft often use a starting point like a character waking to an alarm clock (this is the opposite of an exciting opening) or with someone look into a mirror to describe interiority or the way they look. These are not the most interesting set pieces and readers might start rolling their eyes.

- Too many characters. Keep it simple for the reader to enter your world. You have a whole book (or series!) to introduce everyone. I often see this with clients who are working on fantasy, especially epic fantasy, which usually has a larger cast of characters and an invented place. Think of the opening as a portal – you can only allow so much through at a time.

Openings (both the first paragraph and first sentence) are incredibly important. Don’t overlook how you’re starting your novel because most readers – and that includes agents and editors – might not stick with you if you haven’t grabbed them from page 1.

While drafting, don’t fret if you feel you haven’t nailed the beginning. Just keep writing. It’s incredibly common for a book’s opening to be re-written upon revision. Just keep going until the end. You can come back to edit later.

Other great openings to explore…

*To the men of the internet who love to point out all the ‘great’ books that start with waking, you’re wrong. I recently offered the waking up advice on Twitter (I know, my mistake, I suppose). What proceeded was a screenshot litany of quite boring books where the characters wake, stretch and complain about being awake. These are not interesting books, men of the internet. The Metamorphosis is not about the process of waking up in the morning; it’s about transformation and disruption.

Looking for an editor for your manuscript? Learn more about how I can help and request a quote.

* This post contains affiliate links.

Leave a comment